How the Spanish Flu Went Viral (And Then Got Boring)

What feels most modern about this pandemic – the all-pervasive news coverage – has a precedent in the 1918 Spanish flu that suggests why it’s already tapering.

Despite expert warnings that coronavirus repercussions will extend through summer, politicians aren’t the only ones wondering how much longer even partial lockdowns can last. The trouble isn’t just impatience. Almost two months after the cancellations of events and entertainment nationwide, the sheer inescapability of pandemic discourse raises the question of how much longer we can remain interested enough to follow its advice. The story of the last time a virus went viral shows that our ability to retain attention is essential to maintaining public health as officials ease restrictions, and it provides lessons for staving off fatigue enough to do so while consuming pandemic discourse.

Several writers have noted parallels between the coronavirus pandemic and its most devastating modern predecessor, the Spanish flu, which killed millions worldwide in the final months of 1918 and World War I.1 This comparison is somewhat exaggerated: the Spanish flu proved deadlier and faster-acting. What the two do have in common is that the Spanish flu, like the coronavirus, was a truly global event, in the ways that both the disease and the discourse about it spread. With newspaper data from Chronicling America, we can reveal how. (Open images in new tab for larger versions.)

The newspaper was the primary news format in 1918, but it bore striking resemblance to our contemporary media ecology. Issuing updated editions throughout the day, sharing syndicated articles, and freely reprinting snippets from one another, newspapers had more in common with the continuous speculation, reposting, and retweeting of a Twitter feed. It was a fast-paced technology as amenable to “viral” stories and memes as any in the twenty-first century.

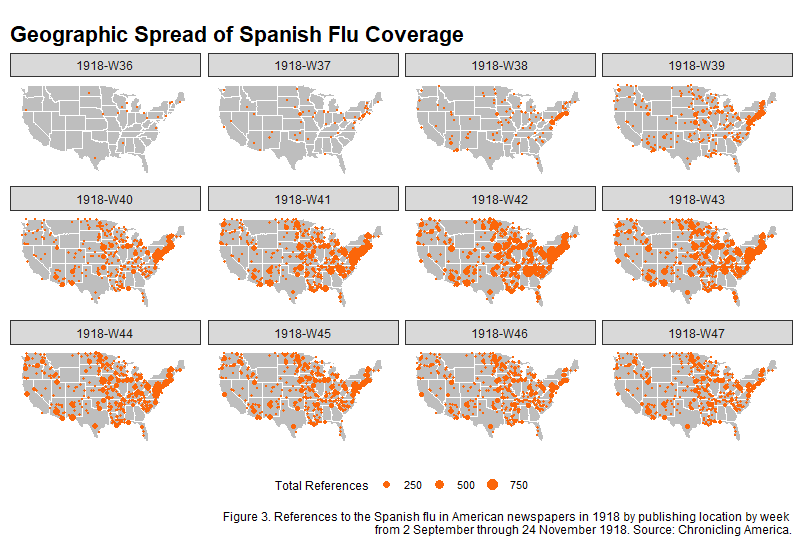

Despite de facto censorship in August and September while the virus gained its foothold, news of the Spanish flu shot through this highly-internetworked media environment in October. Over that exasperated month newspapers referenced the Spanish flu more than twice for every page they printed.2 Initial coverage clustered near the military bases where soldiers brought the unusually-deadly influenza strain back from Europe, but the dissemination of news quickly outpaced that of the virus even with the latter’s head start. The Spanish flu went from sporadic reportage to nationwide ubiquity in mere weeks.3

This experience of total immersion can make pandemic discourse often feel frustratingly like mere sound and fury. All the more so in 1918, when a general lack of precise statistics in circulation fueled even deeper divisions among commentators on how (or whether) to respond to the virus. Every week, American newspapers flooded homes, streets, businesses, and public transit with over half a billion pages.4 The Spanish flu was on every one of them. The result was no less overwhelming than today.

The Spanish flu shows that the best way to make sense of pandemic discourse is by recourse to its very pervasiveness. Quantity can often communicate more than content. In spite of extensive disagreement and misinformation, at first the volume of articles roughly correlated to the number of deaths. The peak in news coverage in mid-October (week 42, beginning with the 14th) in fact slightly preempted the peak in deaths, which would come in late October and early November.

Newspaper coverage immediately began to decline, however, even as the domestic death toll continued rising in November and rebounded in many locations in December and January. Why? Looking to broader patterns rather than specific content illuminates what happens to pandemic discourse as and after it goes viral.

Like today, in 1918 news cycles shaped press as much as conditions did. Even at its height, Spanish flu coverage remained closely related to the number of newspaper pages printed daily (Figure 1). Reports on global pandemics still had to obey norms of what should be printed on particular pages or particular days; conversely, when there were more pages to fill writers relied on the Spanish flu to supply content. The rate of reference held longer at roughly once per page, indicating the degree of news saturation with which editors and readers were more comfortable. Major events expose as much about the way we circulate information as news media informs us about events themselves.

Trends in content shed further light on the rapid climb and brisk drop-off in pandemic discourse. The most reprinted articles drove discussion, inspiring copies and commentary. They tended to fall into three familiar categories, showcasing how little our response has changed: advice for self-isolating, pieces on the cultural repercussions of pandemics, and opportunistic advertisements. (Obituaries and commentary on school or business closures were also common though more locally-specific.) The first two of these types worked in tandem to drive the October peak in total coverage. Advice pieces promised that, if followed, all would be over sooner, while culture pieces attempted to interest readers in the pandemic and their own preventative efforts in the meantime.

It is surprising to see just how little this coverage changed over time, a corroboration of the monotony many feel today. Of all the words used alongside Spanish flu references, only a handful had a standard deviation in week-to-week usage of 4% or higher. There was, though, a subtle yet crucial generic shift. The decline in total coverage corresponded with an increase in advertisements and a decrease in culture pieces. At the same time, the number of front page features declined by almost half from October to January. The Spanish flu was becoming boring.

The decline in coverage was nonetheless experienced at different paces in different parts of the country. The smaller rural papers that initially had been slower to discuss the virus continued grappling with its wake after the leading Northeastern publishing centers tired of virus news and turned their focus elsewhere (Figure 3). We can likely expect a similar coastal/interior disjuncture in the coming months.

We know when something “goes viral” that it won’t remain with us indefinitely. Pandemics, the actual viruses on which that idiom is based, can often feel to the contrary as if they will last forever and change everything. Yet as Spanish flu coverage shows and current events are now repeating, pandemic discourse spikes and recedes much like other major public phenomena. Viruses outlast our interest in them, belying the metaphor of “going viral.” The lessons of the Spanish flu can help us from losing sight of the forest for the trees as we consume pandemic discourse in the months to come – if we can pay attention.

-

“Spanish flu” is a misnomer based on the mistaken impression that the new strain of influenza either originated or was particularly prevalent there. In actuality this impression resulted merely from the fact that the press of Spain, neutral in WWI, was less censored. Readers were largely aware of the inaccuracy. One of the most reprinted articles about the Spanish flu that fall (just missing the cutoff for Figure 4) insisted that there was “no reason to believe that it originated in Spain.” Whether by education or simply the pandemic’s localization, use of “Spanish” to describe this flu declined sharply as coverage increased. (For this reason the data used here encompasses uses of “influenza” as well as “Spanish flu”; see footnote 2.)

↩︎

-

The values for August in Figure 1 and for week 36 in Figure 3, while not part of the typical flu season, are equivalent to the amount of flu coverage found in months that are, namely, January and February 1918. The amount of Spanish flu coverage is thus only trivially offset at most by the “normal” amount of flu coverage. ↩︎

-

The dip in pages per day is the result of Christmas and New Years press holidays, as well as a tendency for the first issues to deteriorate in physical holdings (not the result of current events). ↩︎

-

This is a conservative rough estimate based on summary and circulation figures in N. W. Ayer & Son’s Newspaper Annual (1918). If we multiply 1) the total numbers of weekly, biweekly, triweekly, and daily papers by the number of issues each published per week by 2) an average of 8 pages per issue by 3) 2,000 copies per issue, a very conservative guess taking into account the fact that while many papers had circulations between 500 and 1,500, urban papers often had circulations over 100,000 – the result well exceeds 500,000,000 pages printed per week. ↩︎