The Dedicated Bookstore Predicament

A lot of ink has been spilled over the decline of the dedicated bookstore – stores dedicated “just” or primarily to selling books – amid the rise of online retailers and e-readers in the 21st century. Yet dedicated bookstores were often not the main source of books in the U.S. historically. In fact, that market role was highly contested over the last two centuries.

In the early 20th century, a consumer could buy books from many different types of retailer. The specific focus, stock, clientele, and consumer experience of these different retailer types varied significantly and did much to shape the relationship between consumers (or readers) and books. In this richly varied market, the dedicated bookstore was outplayed on multiple fronts.

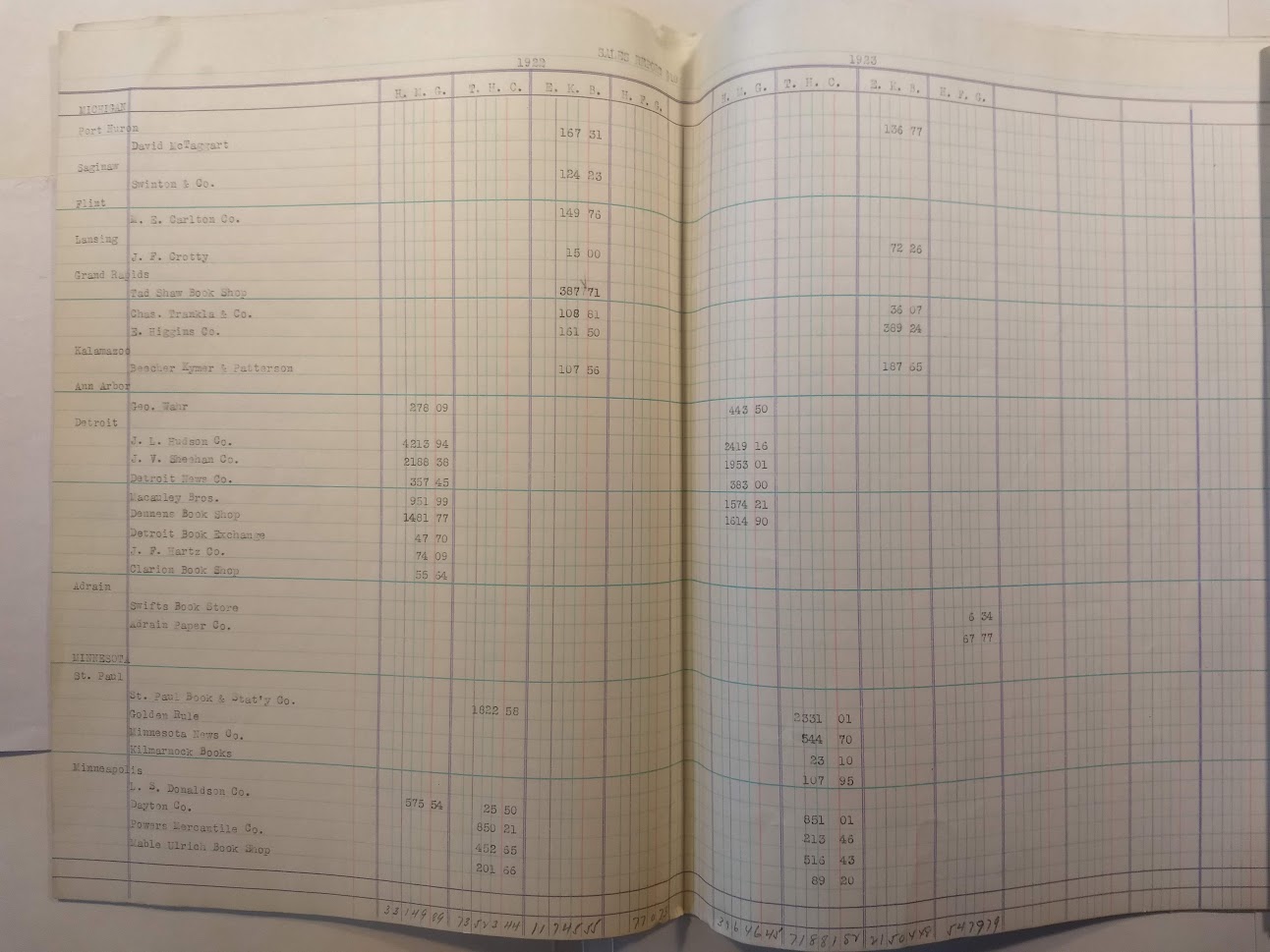

Detailed sales records from J. B. Lippincott Company – one of the era’s largest publishers – show the volume and reach of the book trade with different retailer types.1 I’ve transcribed Lippincott accounts from 1922 and 1923, merged with my existing 1925 Publishers' Weekly bookseller directory metadata. Note that Publishers' Weekly designed many, though not all, of these types to overlap: a Department Store couldn’t also be a News depot, but a bookstore focusing on Juvenile books could focus on Educational or Religious books as well. As such, these figures designate the relative importance of retailer segments rather than the absolute sales of, say, Juvenile books as a genre.2

Wholesalers were the largest purchasers of Lippincott books (Fig. 1); 15% of all sales went through these companies. Wholesalers mostly did not operate retail locations but rather transported and sold books to those that did.3 Retailers that bought a large number of books tended to do business with publishers directly. Retailers that only stocked a modest number of books, such as Gift Stores and Drug Stores, typically bought through Wholesalers rather than buying directly from publishers like Lippincott. Drug Stores had served an important role as booksellers in small-town America in the 19th century, yet the fact that relatively few were listed as booksellers by Publishers' Weekly suggests that their importance to the industry was declining (Fig. 3).

A number of specialized stores stocked large volumes of books on their subjects. These included retailers of Legal, Medical, and Religious goods. The Educational market had grown rapidly over the second half of the 19th century to develop its own distinct retailers, and the Juvenile market was growing enough in the early 20th century that many retailers made it a priority.

Other retailer types were distinguished by the nature of the books they sold. Foreign Language bookstores clustered in cities and often relied on immigrant customers. Old and Rare booksellers – a category that includes sales to other publishers – spent disproportionately more on publisher orders because they often sold expensive special editions (Fig. 2). The same was true of Foreign Language books, which often had to pay translators or came in costlier classics editions, as well as Medical books, which often had expensive illustrations. These market segments did not generate as much publisher revenue overall, but their individual retailers were strong business partners.

Second Hand booksellers were already an important part of this ecosystem (Fig. 3), though by their very nature they were less likely to purchase new titles than their peers (Fig. 2). News depots (as they were often called in the 19th century) or News companies (as they were more often called in the 20th) were the most common book retailer, not unlike the news stores one finds today in airports or (then as now) train stations. News companies often sold newspapers, magazines, stationery, and various other dry goods. They were often smaller, required less capital, and had a broader customer base than other retailer types while still prioritizing print. While Lippincott did good business with a number of News companies, however, its direct penetration into this market was limited: just 7% of News companies bought from Lippincott directly. The rest worked with Wholesalers.

Department Stores disrupted the book retail market upon entering it in the late 1800s. An acrimonious contest flared up in the early 20th century between publishers, leading Department Stores like Macy’s of New York and Wanamaker’s of Philadelphia, and rival bookseller types because Department Stores used books as loss leaders. In other words, they sold books, which had a low per-unit cost, at a loss in order to lure customers in to purchase other more expensive goods with higher markups. This practice – which was by most accounts effective – began to siphon business from other book retailer types, depress the sale price of books in general, and give Department Stores power over publishers.

Lippincott’s sales records illustrate the problem that Department Stores posed for publishers. Department Stores represented the largest single non-Wholesale retail segment for books (Fig. 1). At least 12% of all Lippincott sales were to this group—after all, additional small Department Stores purchased from Lippincott through Wholesalers. Department Stores were no less powerful individually, as they had the second highest average annual sales after Old and Rare booksellers, roughly twice as much as the average News company, Religious, or dedicated Bookstore (Fig. 2). Department Stores squeezed publishers, who couldn’t live without them. That said, not all Department Stores operated the same; 90% of them didn’t buy directly from Lippincott, indicating that Macy’s and Wanamaker’s undercutting practices could not have been ubiquitous (Fig. 3).

What about dedicated Bookstores? Perhaps the most striking aspect of their position in the book retail market is how unstriking it is. Dedicated Bookstores represented a significant 7.5% of Lippincott’s revenue, yet they trailed behind News companies and Department Stores (Fig. 1). They carried less purchasing power at the individual level, where they fell in the middle of the pack behind less-common yet higher-volume retailer types like Foreign, Medical, and even Religious (Fig. 2). And while Bookstores were easily the second-most-common retailer of books, only 9% bought directly from Lippincott’s—meaning that they weren’t especially consistent either (Fig. 3).

Dedicated Bookstores were a major player in the book ecosystem, but they did not define it. They competed in a tight market where other retailer types beat them on affordability, breadth of location, specialized subject matter, and high-margin editions. In this context, dedicated Bookstores could all too easily become jacks of all trades and masters of none. A majority of Americans got their books from other retailers, and this was not entirely due to a lack of dedicated Bookstores in many towns: it also stemmed from a lack in dedicated Bookstores' business model, a lack which continued to plague them into the 21st century even as they became more ubiquitous.4 For all our platitudes about the power of books writ large or reading as a single hobby, books seem to be less of a unifying force in their own right than the subjects they concern or the experiences they complement.

-

“Retail Sales Reports (1922-1924),” Box 40, Series 6B, J. B. Lippincott Company Records, Historical Society of Pennsylvania, PA. ↩︎

-

The ambiguity and overlap of these categories, combined with the black box of Wholesaler sales, should both be taken as qualifiers for this post. In a world where retail chains were much less common, this kind of ambiguity and overlap was a natural part of the market. Religious retailers could easily sell bestselling novels with strong religious themes while dedicated Bookstores naturally sold popular religious books, such that classifying a retailer exclusively as one or the other would be impossible. This is why I stress thinking of these categories as indicating the relative importance of market segments: they don’t imply the total sales of specific genres or the strict adherence to uniform business models (even though for some categories this was nearly the case). ↩︎

-

Unfortunately, I am not aware of any existing Wholesaler sales records pertaining to books. If you are, for goodness' sake, send me an email. ↩︎

-

If you liked this post, you may also be interested in my previous on “Seasonal and Economic Cycles in the Publishing Industry." If you didn’t, you probably should’ve stopped reading sooner. ↩︎